View larger

View larger

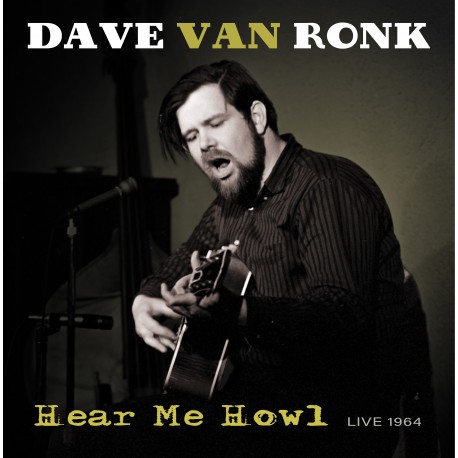

Dave Van Ronk: Hear Me Howl

New product

Dave Van Ronk influenced such folk musicians as Bob Dylan and Tom Paxton, plus the Coen Brother's movie "Inside Llewyn Davis."

More info

Track List:

- That’ll Never Happen No More

- God Bless The Child

- Baby Let Me Lay It On You

- The Song Of Wandering Aengus

- Frankie’s Blues

- Two Trains Running

- Tell Old Bill

- Mr. Noah

- One Meatball

- Cocaine Blues

- St. James Infirmary

The world was an interesting place in 1964. The Beatles made their first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, Lyndon Johnson declared war on poverty, Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali and the first Ford Mustang rolled off the assembly line. England and France inked a deal to build a connecting tunnel, Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life in prison, and the Rolling Stones recorded at Chess Studios in Chicago. The Civil Rights Act was signed into law, and three young men disappeared in Mississippi. Health warnings were first published on cigarette packages, and the U.S. began bombing North Vietnam. The Free Speech Movement was born at the University of California in Berkeley, Dr. Martin Luther King won the Nobel Peace Prize, Canada adopted the Maple Leaf flag, and the U.S. held nuclear testing in Nevada. While all this was going on, Dave Van Ronk was recording the songs you hear on this album.

Already a veteran at 28 at the time of this concert, Van Ronk had begun his “career” a decade earlier, pulled as by a magnet into the world of jazz. The rhythms, the discipline, the history and the improvisations of jazz would never leave him. His move from his native Brooklyn to Greenwich Village, and the burgeoning coffeehouse scene he found there, shifted his focus to folk music; although he would go back to traditional jazz from time to time, he soon found his niche as the unofficial “Mayor of MacDougal Street” a good fit, and settled in.

One of Dave’s oldest friends from those early days in the Village is singer and songwriter Tom Paxton, still actively writing, recording and touring at 77. He remembers, “I met Dave Van Ronk in the summer of 1960. I was still in the Army, based at Fort Dix, and was coming into the Village on weekend passes. Dave was doing the booking at The Commons, a coffeehouse directly across the street from The Gaslight and down a long corridor. Tres boheme! The pay was a huge $10.00 a night, as I recall, and while that may not seem like much, $20.00 meant I wouldn’t have to suffer the mess hall lunches the following week but could splurge at the PX. Bliss.

“Dave and I hit it off right away — it’s hard to say why. A cynical Village veteran and a hayseed from Oklahoma wouldn’t seem a match on paper, but we got along from the start. I asked a lot of questions and Dave had thousands of answers. He’d certainly lived a lot more than most of us newcomers had done; been to sea and all that, and was a huge reader with a great memory. I think he had a broader perspective than most of us had—certainly more than I did. Above all, he was a critical thinker, which I was not and have never become.

“But above all, he laughed a lot. I get along best with people who laugh a lot, and Dave was a world-class laugher. He laughed at fools, he laughed at my jokes—what more can one require of a friend? He was my best man when Midge and I were married and he is still my best man.”

Van Ronk’s living room became a salon of sorts, and younger musicians (notably Bob Dylan) camped on his couch, took guitar lessons and shared stages with him. Others, again including Dylan, would later take his influence (and sometimes his repertoire) farther than he ever did. But 1964 found him in his prime, at the top of his game and with a solid body of work both already behind him and yet to come.

The songs heard here were recorded half a century ago, on October 20, 1964, at a concert at the University of Indiana at Bloomington, a venue that does much to explain the excellence of the recorded sound quality. Unlike the coffeehouses and nightclubs where Dave often played, the University had what today would be called a performing arts center, and its auditorium had professional quality sound and lighting. The selections are all part of his regular repertoire of the time, and include blues, folk songs, old traditional numbers he had (re)arranged to suit his own style, and covers of songs by Billie Holiday and Blind Blake, among others. The sequencing here is exactly the way Dave conceived of it, and he was always a careful “constructor” of his sets. He rarely played two songs in a row in the same key, or the same tempo, and he sprinkled instrumentals throughout the evening, but again, never two in a row. Rather than alter Dave’s concept of how the evening would best flow, we’ve chosen to leave it exactly as it was performed.

Hearing his conversational between—songs rap gives a good flavor of exactly what his live shows were like. He had a great sense of humor, as Tom Paxton notes above, but never took himself too seriously. He was expository, but not didactic, and never talked down to his audiences. He figured if they didn’t know who Blind Blake was at the beginning of his show, they certainly would by the end.

And then there was the movie. It’s a shame that Dave didn’t live to see the fuss, the wrangling and the hilarity it caused among his friends. The film, made by the Coen brothers, was called “Inside Llewyn Davis,” the title being loosely based on one of Dave’s early LPs, which was called “Inside Dave Van Ronk.” The film itself was “loosely based” on Dave’s memoirs, and the title character was “loosely based” on Dave. About the only things his friends agree on was that the film was helpful in (re)introducing his music to the world, since a fair number of people who had never bought a Van Ronk LP in their lives headed for their purveyor of choice after seeing the film. There is no indication that any of them were disappointed.

Dave adapted his arrangement of “That’ll Never Happen No More” from a 1927 recording by Blind Blake, and he most likely learned “One Meat Ball” from the singing of Josh White. Billie Holiday co-wrote “God Bless the Child” in 1939 and recorded it in 1941; this was one of many tunes that go back to Dave’s days in the world of jazz. For those who collect ephemera, this album contains the only known performance of Dave taking a whistling break on “Cocaine,” one of several songs here he learned from Reverend Gary Davis . Dave’s version of “Cocaine” would later be covered by Jackson Browne. “Baby Let Me Follow You Down” was a collaborative effort; it began life as a song in Reverand Davis’ repertoire, and was adapted and new verses written by Dave and his good friend Eric von Schmidt. Bob Dylan learned it from Van Ronk, von Schmidt or both, and it subsequently appeared on Dylan’s debut album for Columbia.

At the time of his death on February 10, 2002, Dave had been working for several years with his former guitar student and friend Elijah Wald on a memoir, which ,Wald completed and published three years later. lt bring’s Dave’s voice to life, as he tells funny, irreverent and witty vignettes of his storied life and career. Look for “The Mayor of MacDougal Street,’’ by Dave Van Ronk with Elijah Wald. Canibridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2005. In a nod to Dave’s universal appeal, it has so far been translated into German, Italian, French, and Japanese.