View larger

View larger

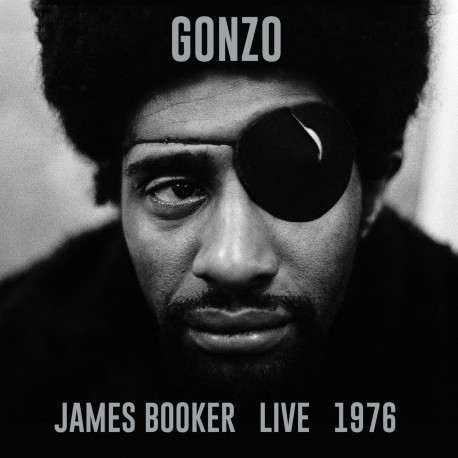

Gonzo: James Booker, Live 1976

New product

More info

DISC ONE

- Life

- One Helluva Nerve

- United Our Thing Will Stand

- Slowly But Surely

- Too Much Blues

- Junko Partner

- Classified

- Stormy Monday

- Sixty Minute Man

- Please Send Me Someone To Love

- Desitively Bannaroo/Right Place, Wrong Time

- Tico Tico

- Save Your Love For Me/Lonely Avenue

- Love Monkey/Feel So Bad

- Besame Mucho

- All By Myself/Let The Four Winds Blow

DISC TWO

- Ora

- Baby Won’t You Please Come Home

- Sixty Minute Man

- Please Send Me Someone To Love

- Am I Getting Through To You

- Slowly But Surely

- Junco Partner

- People Get Ready

- Classified

- I’ll Be Seeing You

- Rockin’ Pneumonia & The Boogie Woogie Flu

- Let’s Make A Better World

- Tipitina

- Let Them Talk

- Baby Face

- Hound Dog

- Baby Won’t You Please Come Home

- Gonzo

BONUS TRACK EP

19. Gonzo

20. Cool Turkey

21. Tubby Part 1

James Booker’s music could’ve come from nowhere but New Orleans. The Crescent City welcomed James Carroll Booker III on December 17, 1939 and bid him adieu November 8, 1983. His welcome had worn thin by the time he passed: In a city famous for honoring beloved musicians with spirited sendoffs, Booker’s funeral was sparsely attended. His edgy, erratic behavior had alienated and exasperated many who were saddened but little surprised by his death. New Orleans record dealer Jim Russell observed: “Booker lived 430 years in 43 years.” Between his arrival and departure there was much madness, joy and despair, all writ large on Booker’s kinetic keyboard.

The piano is a memory machine. In an era when even synthesizers can seem anachronistic, the physicality of a piano’s sound floods listeners with deep neural associations. Stand near an acoustic piano while its played and you feel its bass notes in the soles of your feet: You experience it ` toe to head.’ It can’t help but make a profound impression on children, who are of a scale to explore the machinery that makes the sound: a complex interaction of string and wood and felt and metal and more. Seeing, hearing, feeling: the piano offers a sensory feast. Few places have ever served that feast as well as New Orleans.

“New Orleans was the stomping grounds for all the greatest pianists in the country,” Jelly Roll Morton recalled in Alan Lomax’s book, Mr. Jelly Roll (1950). Looking back at the early days of the 20th century, Morton said: “We had them from all parts of the world, because there were more jobs for pianists than any other ten places in the world. The sporting-houses needed professors, and we had so many different styles that whenever you came to New Orleans, it wouldn’t make any difference that you just came from Paris or any part of England, Europe, any place—whatever your tunes were over there, we played them in New Orleans.”

In a radio interview, Allen Toussaint recalls being floored by a twelve-year-old Booker’s rendition of keyboard classics: “He was playing so much piano! For a boy to be playing that much was outrageous! He was playing Bach and Rachmaninoff and some funk, too.”

A 1958 Times-Picayune article recounts the reaction of classical keyboard king Arthur Rubinstein to an eighteen-year-old Booker’s post-concert performance for the Maestro: “I could never play that,” a flabbergasted Rubinstein said, “…never at that tempo.” The performances here find Booker glibly tossing off references to the classics (`Flight of the Bumblebee’ buzzes briefly in `One Helluva Nerve’ and even in `Tico Tico’) and a range of repertoire (standards, Latin tunes, R&B) that confirms Morton’s assertion: the best New Orleans pianists played everything.

Sidemen kept up with Booker as best they could.

“He was totally stream of consciousness,” bassist Reggie Scanlan said in a radio interview. “It would enter his brain and come out of his hands like that! He could play Mozart pieces within `Junco Partner.’ He had the ability to make that seem like it was just a logical transition.”

Booker’s genius defied logic and circumstance. He was the son of a Texas-born Baptist minister who had been a dancer prior to receiving `the calling,’ which led him to New Orleans. The elder Booker played piano; his wife sang in the choir. The couple sent son James and daughter Betty Jean to live with an aunt in the Mississippi town of Bay St. Louis when both were very young. There, James attended Catholic school and commenced classical piano studies at age six, quickly proving himself a prodigy. Nothing deterred his musical progress, but a terrible accident at age nine cast a pall over the rest of his life. Struck by an ambulance and dragged 30 agonizing feet, his leg was broken multiple places (he would limp the rest of his life). Booker was given morphine for his pain, and he later blamed that for causing his future predilection towards narcotics and alcohol.

After Booker Sr. died in 1953, James and his sister came home to their mother in New Orleans. Betty Jean had become an outstanding singer and landed a spot warbling gospel on radio station WMRY on Sunday afternoons. Booker tagged along, and when the station managers heard him play piano, they gave Booker Boy & the Rhythmaires a spot on a Saturday R&B show. Producer/bandleader Dave Bartholomew caught the act and signed `Little Booker’ to record for Imperial in 1954. “Doin’ the Hambone” was no hit, but hearing the 14-year-old Booker’s piano today offers tantalizing hints of coming attractions.

Booker’s facility for playing everything and in all styles proved fortuitous. When Fats Domino’s road schedule left him little time to record when home, Bartholomew pre-recorded the band with Booker taking Fats’ role on piano. That left only Domino’s vocals to track when he could be led into the studio. (A Fats medley closes Disc One of this collection.) Conversely, another star’s reluctance to tour was a boon to Booker. In Huey `Piano’ Smith and the Rocking Pneumonia Blues (Louisiana State University Press), John Wirt writes: “…the extraordinarily talented, eclectic, and eccentric James Booker played piano for the Clowns after Huey grew both weary and wary of the road…The eighteen-year-old Booker had studied classical piano and had been mentored by the similarly versatile New Orleans piano great Tuts Washington…`When Huey didn’t come out,’ [tenor saxophonist] James Rivers remembered, `then there was Booker, because Booker could play all of Huey’s stuff that people hear on the record. Booker not only could play Huey Smith, Booker could play everybody else, too. Man, after some gigs we’d go on a jam session and Booker would be cleaning cats out left and right.” (The performance on Disc Two of Smith’s signature song is from a previously unreleased BBC session.)

Booker also hit the road with Joe Tex, Shirley & Lee, and Earl King in the late 1950s. His talent caught the ear of Houston entrepreneur Don Robey, whose Peacock label recorded Booker’s only chart success. As a child, Booker played gospel organ in his Dad’s church. The Hammond B3 organ became a hot pop-jazz property and Booker’s vehicle for his one big score, “Gonzo,” an instrumental named for a character in the 1960 dope exploitation flick The Pusher. In that golden age of rock instrumentals “Gonzo” made it to #3 on the R&B chart. The movie or the tune or both inspired Hunter S. Thompson to dub his writing style `Gonzo journalism.’ (The original “Gonzo” and two other tunes of that era appear at the end of this collection’s Disc Two.)

Booker stayed busy on the road and in the studio in coming years as sideman to a diverse crowd, everyone from Bobby `Blue’ Bland to the Doobie Brothers. Jerry Wexler brought him to Atlantic to record with King Curtis and Aretha Franklin, who waxed Booker’s “So Swell When You’re Well.” But his road forked when busted for heroin possession outside of the landmark Dew Drop Inn. (Dates vary in accounts, though the year most commonly cited is 1970.) Booker was sentenced to Louisiana’s infamous Angola Prison, where he reportedly worked in the library and helped develop a music program. His `good behavior’ led to his parole after serving just six months. (“Long enough,” Booker once remarked, “ to feel the iron in the bars getting into my head.”) As soon as he was out, Booker again sought session and road work, first in New York, then in Los Angeles. (This was a parole violation.) Among his gigs was playing organ in Dr. John’s Bonnaroo Revue in 1974, eighteen years after Booker taught “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie” to a sixteen-year-old Mac Rebennack, then a guitar player. Recently, Dr. John famously dubbed Booker “the best black, gay, one-eyed junkie piano genius New Orleans has ever produced.”

In the early 1970s, Booker began manifesting textbook paranoia, complaining of CIA plots against him. At the same time his musical star was arise: a 1975 appearance at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival created a buzz that helped him locally and, soon, internationally. In the All Music Guide, Bruce Boyd Raeburn writes: “Booker’s performances at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festivals took on the trappings of legendary `happenings,’ and he often spent his festival earnings to arrive in style, pulling up to the stage in a rented Rolls Royce and attired in costumes befitting the `Piano Prince of New Orleans,’ complete with a cape.”

A Rolls, a cape, and a ticket for Europe! The year America celebrated its Bicentennial, Europe beckoned Booker. He’d already recorded with everyone from the Queen of Soul to an ex-Beatle (Ringo), but it’s hard not to deem his European solo performances his career’s high water mark. Film maker Lila Keber, whose Bayou Maharajah: The Tragic Genius of James Booker is the first documentary devoted to `the mystery’ of Booker, agrees. “I think that Booker felt he was being taken seriously in Europe,” she told The Oxford American, “and it made him think of himself differently and improved the quality of his music. He needed the energy of the audience to feed off. Maybe it’s because Europeans come from that classical tradition, so they understood what he was doing musically, and that what he was playing was an entirely new approach to the instrument. So many European jazz fans have told me that jazz is the art of the twentieth century, but I can’t think of too many Americans who would say that. Europeans sit down and pay attention, and James Booker’s music is concert-hall worthy to them.”

Concert halls, festival stages, and clubs all welcomed Booker in Europe. Among the venues was Hamburg’s Onkel Pö, then one of several host sites for the city’s New Jazz Festival. Horace Silver and Chet Baker are among a lengthy `who’s who’ of jazz legends who played Onkel Pö’s. Whatever Hamburg jazz fans knew of, or expected from James Booker in 1976, they were obviously delighted by what they got. Their enthusiasm tickled Booker, heard in his playful `Dankeschöns’ that precede “One Helluva Nerve.” The eighteen tracks recorded at Onkel Pö’s in October 1976 appear together for the first time on one collection here. They show the range of Booker’s material, from a Bessie Smith song of the 1920s, “Baby Won’t You Please Come Home” (though Booker’s source was surely Ray Charles), to Booker originals like “Classified,” which lent its name to his final studio album. Eight additional `live’ tracks performed three nights later offer both new songs (a moving “People Get Ready”) and confirmation of the oft-heard claim that Booker never played any song the same way twice!

One to which he was deeply attached was Percy Mayfield’s “Please Send Me Someone to Love.” Bruce Raeburn, who once played drums for Booker, observes: “Whatever pain that man was carrying around, a song like that was perfect for him to bring it out and maybe achieve some kind of catharsis.” It shouldn’t be forgotten that Booker was son of a preacher/pianist father and gospel-singing mother. His piano and vocals alike are drenched in `church.’ He even brings `church’ to blues ballads like “Stormy Monday.”

Eight 1978 performances recorded at London’s legendary Maida Vale Studios for the BBC are released here for the first time. They find Booker referencing his home team—Professor Longhair (“Tipitina”), Fats (“Baby Face”) and Huey (“Rockin’ Pneumonia…”)—reprising his one hit (“Gonzo”), and turning in a moving Little Willie John cover (“Let Them Talk”). But none of it’s more sublime than his relaxed, sharply focused solo on “Baby Won’t You Please Come Home.”

The final five years of his life Booker spent in New Orleans, where his European triumphs bought him little regard. Recollections of Booker from his last years offer Jekyll & Hyde contrasts: on the one hand, there’s the man often described as fragile and lonely. Singer-songwriter Rickie Lee Jones wrote: “He was very shy, withdrawn, but seemed to me to be just a man who had dug a place too deep inside himself to stay in and now it was too far to come up to bother with visiting with people.” On the other hand, there are the `wild man’ anecdotes, not the least of them the one in which Booker walks onstage clad only in a giant diaper, pulls a pistol from it, puts its barrel to his temple and proclaims: “If someone doesn’t give me some fuckin’ cocaine right now, I’m pullin’ the fuckin’ trigger!”

The strange case of J.C. (as his family called him) Booker begs hoary old questions about self-destructive behavior and creativity, madness and genius. There are all manner of unlikely plot twists in Booker’s legacy. Filmmaker Lila Keber points to a glaring one: “The story of James Booker and Harry Connick Senior is one of those `only-in-New-Orleans’ myths,” she told the Oxford American. “The acting district attorney gets this renowned drug user with one eye to teach his little half-pint son how to play the piano. That’s bizarre. Then the kid grows up to be Harry Connick Jr.? That’s even more surreal on top of everything else.”

Surrealism came from Europe, where James Booker was loved, and might have expatriated. No shortage of precedent on that move among blues pianists: Memphis Slim settled in France, Eddie Boyd, Finland, the Crescent City’s Champion Jack Dupree, Germany. Instead, Booker returned home to generally benign neglect. He died sitting in a wheelchair waiting for a doctor at the New Orleans Charity Hospital. Pathetic.

30 years after his passing, a documentary about Booker played to acclaim at a handful of film festivals, though for sundry reasons (the expense of licensing songs chief among them) most of us may never see Lila Keber’s 2013 production Bayou Maharajah: The Tragic Genius of James Booker. But it’s tribute to the power of Booker’s music that a young woman with no initial `in’ to his world became obsessed with pursuing this phantom. Keber spent years tracking down performance footage and interviewing surviving Booker cohorts, so she’s earned the last word. “I feel like there was no realm in which Booker was in control,” she told Rolling Stone, “except the music. It seemed like the whole world could be crumbling around him, or his relation to reality, but as long as he was sitting in front of the piano, he was in charge of something.”

—Mark Humphrey