View larger

View larger

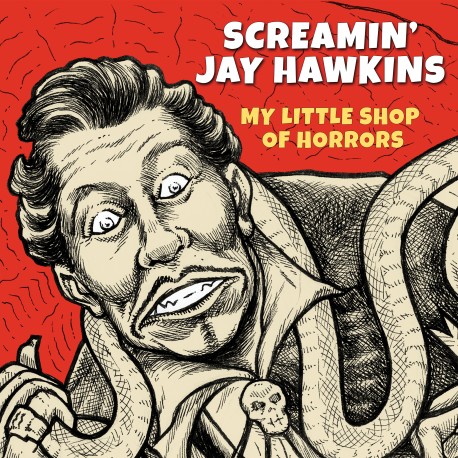

Screamin' Jay Hawkins: My Little Shop of Horrors

New product

More info

Track List:

- I PUT A SPELL ON YOU

- PORTRAIT OF A MAN

- WHAT’S GONNA HAPPEN ON THE 8TH DAY

- WE LOVE

- PLEASE DON’T LEAVE ME

- I DON’T KNOW

- WHAT GOOD IS IT PT. 1

- DON’T DECEIVE ME

- ASHES

- IT’S ONLY MAKE BELIEVE

- GUESS WHO

- SAME DAMN THING

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins was outrageous when it was still a dangerous course of action.

Long before Arthur Brown, Alice Cooper, and Ozzy Osbourne escorted rock theatrics to new heights, Jay hit the fabled Apollo Theatre stage hidden inside a coffin, busting out to shriek demented couplets about voodoo spells, little demons, and alligator wine. Maturity never mellowed him: he subsequently emitted the flatulent tirade “Constipation Blues,” and in front of a few hundred thousand folks at the 1996 Chicago Blues Festival, Hawkins strained it out with gassy gusto while preposterously seated on a custom-made rollaway commode.

First and foremost, Hawkins was a visual act. Hard as it is ta believe, he never notched a national hit. Even “I Put A Spell On You,” his seminal 1956 waxing for OKeh Records, failed to chart, though everyone from diva Nina Simone to Animals organist Alan Price to Creedence Clearwater Revival later paid tribute with remakes. Even after he passed away on February 12, 2000 at age 70, his immense legend continued to grow. A website was instituted to trace how many children he had fathered out or wedlock during his decades of touring, the number now exceeding 75. Yes, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins was a bigger-than-life figure, prolific in many ways.

Born July 18, 1929 in Cleveland, Ohio, Jalacy Hawkins was an orphan who was raised by a Blackfoot Indian known as Mama Randolph. He channeled his youthful volatility into a successful boxing career, reportedly winning the Alaskan middleweight championship in 1949. His pugilistic tendencies carried over into his musical relationships later on; he bragged about whacking sax honker Red Prysock over the head with a folding chair during a disagreement about his act, and he socked the Drifters’ Charlie Thomas in the mouth after the group jokingly locked Hawkins in his coffin at the Apollo (nearly asphyxiating Hawkins in the process).

Perhaps Jay wouldn’t have carried so much aggression around with him had he been allowed to unleash his prodigious pipes on the classics. “My idol ls Paul Robeson, and I always wanted to do opera. But opera don’t know choice,” he explained in 1981. “I attribute my screaming to the fact that I have an operatic voice, and I can make use of it in the blues. Hollerin’ and holdin’ a note. That’s the only thing I can attribute that to.”

Jay earned his stage moniker in Charleston, Va. in 1950. “I wasn’t even out of the service yet. I was home on leave. I had just got back from Germany,” he said. “Spent three years over there. I joined this show. They wanted a singer, just a blues singer. So I joined this show. As a matter of fact, I was an emcee too. I brought people on, then I did my own little act. This girl was drunk. I mean, it’s not that she wasn’t enjoying the music, but she was drunk too. She llked it enough to keep hollering, ‘Scream, Jay! Scream! Scream, baby!’ And I liked the title. I said. ‘There’s my name! Screamin’ Jay Hawkins!’ I found out there’s very few people in the world can keep screamin’ four or five one-hour shows a day for seven days without going hoarse.”

Upon completing his military stint In 1951, Hawkins—who developed into a serviceable pianist—joined guitarist Tiny Grimes’ combo. “I worked for him a year for $30 a week, and only seen it twice,” claimed Hawkins. “Ate hot dogs, drove his car, I was his bodyguard, his dog walker, his chauffeur. I carried some of his money. I was also his other only musician sometimes. We didn’t have the other men in the band, so we’d go to another city and go to the musician’s union and get the rest of the musicians. Then we’d rehearse ‘em and take ‘em to where we had to play. Then him and I would go hit the road again.” Jay debuted on wax in 1952 fronting Grimes’ Rocking Highlanders on “Why Did You Waste My Time” for Philly-based Gotham Records.

In 1953, Jay made his first sides under his own name for tiny Timely Records in New York, the raucous “Baptize Me In Wine” and its followup “I Found My Way To Wine” a fair indication of the lunacy to follow (the much larger Apollo imprint picked them up for national consumption). Moving to Mercuryin 1955, his foreboding “[She Put The] Wamee [On Mel]” was a direct precursor to “I Put A Spell On You.” Cut in September ot ‘56 for Columbia’s OKeh diskery, “Spell” was originally envisioned by writer Hawkins as a sweet love song. It ended up as a grunt-and-groan-filled minor-key rant that was banned by many radio stations. Jay got so drunk at the date that Columbia A&R man Arnold Maxin had to latter fill him in on what happened.

“He says. ‘No, Jay, a gallon of wine was brought in, and we decided ‘I Put A Spell On You’ should not be a love ballad. It was something more like a novelty act. You didn’t get drunk—you passed out! Every once in a while, while we were playing the music, you would decide to come in. We recorded all night waiting on you. And you took your time. You laid on the floor, you rolled over. And then 10 days after that, when I gave you the record and you listened to it, you could not believe it!”’ said Hawkins who was supported by New York session aces Sam “The Man’” Taylor on sax and guitarist Mickey Baker on the fateful date. “I was under the impression for the first 22 years of my life after that that I had to be that drunk to go on the stage and do ‘I Put A Spell On You’ before I finally stopped drinking all together.”

Deranged genius that he was, Hawkins predictably found mainstream success extremely elusive during the Eisenhower era, even with a major label in his corner. He mimed “Frenzy,” his third OKeh single, in the 1957 Alan Freed bio flick Mister Rock and Roll while outfitted as an African warrior, complete with loincloth, sandals, and a spear (alas, his segment ended up on the cutting room floor). It was Freed that convinced the superstitious Hawkins to climb into the coffin that became his macabre trademark.

“Alan Freed kept throwing $100 bills down on my dresser, saying, ‘You will do it.’ I said, ‘You’re full of shit. Not me. No black dude gets in no coffin alIve, man. They don’t expect to get out!’” recalled Hawkins. “But them $100 bills got heavy and thick and looked good, you know. I’m used to splittin’ my money with the booking agent and wlth my manager. Then I take my share. But his money I didn’t split with nobody. He just kept throwing out hundreds ‘til finally he hit two grand I told him, I’ll do it. I’ll try it.’”

The surreal rockers “Alligator Wine,” Yellow Coat,” and Hong Kong,” all cut in 1957 for OKeh or its sister Epic logo, were too wonderfully weird to locate an audience. During the ‘60s, Jay bounced from label to label before landing on Mercury’s Philips subsidiary in 1969 and waxing ‘Constipation Blues.’ “I wrote that tune on a roll of toilet paper,” he said. “I wrote ‘Constipation Blues’ when I was in Hawaii and I was constipated. I was in the hospital. And I didn’t have no paper, but I had a pencil. So I took the toilet paper roll off, and started writing on that.”

Jay journeyed to Nashville in 1973 to record this set, a coterie of Music Row country pickers somehow locating common musical ground with the R&B-shouting wildman. The session was led by Tommy Allsup, formerly Buddy Holly’s lead guitarist (Allsup gave up his seat to Ritchie Valens for the tragic February 3, 1959 plane ride that killed Holly, Valens, and the Big Bopper), though Allsup is credited as playing string bass for Jay. Chip Young and Jimmy Kovards shared guitar duties. Tony Migliario handled keyboards, Joe Alley played electric bass, and Kenny Malone was on drums. Jay’s wife Ginny was on hand to pitch in on vocals.

Unwittingly providing his epitaph, Hawkins asked to be remembered “as somebody who gave people something different, other that the same thing most singers do—stand up and sing their hit records. I tried to entertain people. I would like to be known, really, as an entrepreneur, more than just a singer or a musician.”

You always will be, Jay.

—Bill Dahl

Source: Blues Unlimited No. 121, Sept.-Oct. 1976, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins,” by Norbert Hess