More info

Track List:

1. Highway To Heaven (3:50)

The O’Neal Twins and the Interfaith Choir

2. Singing In My Soul (2:24)

Willie Mae Ford Smith

3. What Manner Of Man (6:23)

Willie Mae Ford Smith

4. When I’ve Done My Best (2:29)

Thomas A. Dorsey

5. Take My Hand, Precious Lord (2:21)

Mahalia Jackson

6. I’m His Child (3:44)

Zella Jackson Price

7. He Chose Me (4:40)

The O’Neal Twins

8. No Ways Tired (5:24)

Delois Barrett Campbell and the Barrett Sisters

9. Jesus Dropped The Charges (4:27)

The O’Neal Twins and The Interfaith Choir

10. I’ll Never Turn Back (4:33)

Willie Mae Ford SMith and family

11. The Storm Is Passing Over (4:28)

Delois Barrett Campbell and the Barrett Sisters

12. It’s Gonna Rain (4:44)

The O’Neal Twins

13. He Brought Us (6:10)

Delois Barrett Campbell and the Barrett Sisters

14. Take My Hand Precious Lord (5:10)

Thomas A. Dorsey

15. CanaAn (10:18)

Willie Mae Ford Smith

BONUS TRACKS

16. I’d Trade A Lifetime (2:24)

The O’Neal Twins

17. We Are Blessed (2:17)

Delois Barrett Campbell

18. Say A Little Prayer For Me (3:28)

Zella Jackson Price

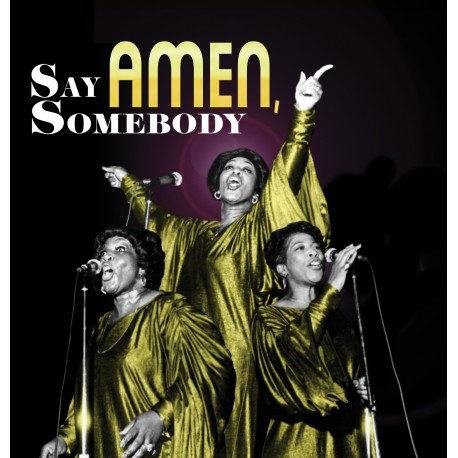

Say Amen, Somebody is an epochal film, produced not a moment too soon. It documents the Golden Age of Gospel Music in its dying hour and pays homage to the music’s pioneers in their extreme old age. Though Willie Mae Ford Smith, Thomas A. Dorsey and Sallie Martin lived years after 1980, they would never again be strong enough to both recall and embody the soul of gospel. In the language of the church, each of them had a charge to keep and a story to tell.

The suave confidence and easy command of the camera of these apparent amateurs astonished early critics like Pauline Kael. What these critics didn’t realize is that Smith, Dorsey, and Martin had been legends in their own community for decades. George Nierenberg’s greatest strength is his implicit recognition that gospel needs no apology: his stars are indeed very great stars. Not because they anticipated rock and roll or soul or hip-hop by three or four generations, which is true but irrelevant. Nierenberg loves his people, as do we, because they are the most generous of artists, making music to lift spirits here, save souls there, not for very much money, as they say, “not for form or fashion,” but for the simple joy of it.

The music they helped create wasn’t even called gospel when they first started performing it. Though the term has become a shorthand for every kind of vernacular religious music, during the form’s inception it went by other names: 11sacred,’1 “religious,” “jubilee,” (after a style of quartet singing that flourished during the l 930’s - Willie Mae Ford Smith made her debut singing in a female quartet, The Ford Sisters); “sanctified” after the worship style of the Pentecostal church (with one such church, Sallie Martin would make her recording debut in 1929) but most often, “spiritual.” As late as 1958, the pioneer gospel labels would refer to their religious recordings as “Spirituals.” True to a form that is constantly reshaping itself, by the early I 960s, when the world started calling it Gospel, the music had turned into something new, later fecklessly dubbed “Contemporary Gospel” (the formerly “Spiritual” was now called, almostdismissively, “Traditional Gospel”). This movie’s stars observed all these developments while remaining true to the music as they had first performed it. There’s an undercurrent throughout the film that despairs over the commercialization that comes with charging tickets for a religious experience. But clearly the debate is as much aesthetic as ideological.

The salient devices of church singing — the moans, falsetto hollers, growls, musical recitatif, extravagant shifts in vocal range and dynamics, a fervent intensity that turned all matters deadly serious, though without sacrificing a sense of irony and even high comedy -- were recognized in the nineteenth century. They can all be heard in early recordings and were so widely assimilated that, by 1914, when Al Jolson introduced Irving Berlin’s “Revival Day,” he could presume that everyone understood the kind of behavior he was singing about.

But it was during the 1920s that a new kind of professionalism swept the church. Certainly when Thomas A. Dorsey -- the minister’s son turned “Georgia Tom,” double-entrendre blues lyricist par excellence -- returned to the church, he brought some jazz with him. His role as “The Father of Gospel Music” is indisputable (Sallie Martin, his troubadour, was “The Mother”), and he may even have given the new sound its name; “before that, they used to call them evangelical songs” (a term that seldom if ever appeared on records, though it does on sheet music). But consider that Dorsey’s childhood friends, Reverend J. M. Gates and Clara Hudman (later known as The Georgia Peach) were big record sellers already, that sanctified congregations were swinging their shout songs to huge acclaim, and that sanctified musicians like the guitarist Blind Willie Johnson and pianist Elder Charles Beck were recording in a style that beat the world at its own game. The music was headed in the direction of modern gospel; Dorsey simply hastened its pace.

He couldn’t have done it without allies, most of whom were female. Sallie Martinwas never a great vocalist (“they say all I do is talk and shake my leg,” she might grumble, “but I’ve gone pretty far with the little God gave me”), but she had the business savvy of a CEO.

Her vision of gospel as a business proposition (“I told him, man, you got something and you don’t know what to do with it,”) appealed to Dorsey. Their boldest step was to turn gospel into an institution. They did so by conceiving The National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses, a frank imitation of the National Baptist Convention. It was an inspired concept. (when Sallie Martin and Willie Mae Ford Smith battle over where the convention actually began, it’s no petty dispute.) They had literally nationalized the music, making the annual convention the focus of singers scattered from New York to Birmingham, Alabama. Willie Mac Ford Smith founded the Convention’s Soloist Bureau, by which means she assured that the individual artist would be as recognized as the larger ensemble. Far more than Sallie Martin, whose greatest influence was mercantile, Mother Smith became the model for later soloists, among them Mahalia Jackson (whom Dorsey chose to replace Sallie Martin, after she quit him to start her own publishing firm). Among Dorsey’s earliest disciples was Roberta Martin (no relation to Sallie; indeed Roberta, along with Mahalia, were two of Sallie’s dearest enemies). She would become the most influential of gospel pianists and the director of the first modern gospel group, the eponymously-named Roberta Martin Singers. And among her discoveries would be Delois Barrett Campbell, the brilliant soprano, whose work with The Barrett Sisters provides some of this movie’s most thrilling moments.

You couldn’t write the history of gospel music without these people.

Thomas A. Dorsey’s name for Mother Smith was “Peach”: she renamed Mrs. Dorsey, “Kitten.” He also once allowed that, while The Georgia Peach could have been another Bessie Smith, the young Willie Mae Ford Smith could have out sung The Empress of the Blues.

Not that Mother Smith, the model of a consecrated gospel singer, would have gone into blues. Yet “before I was saved, I used to have a ball listening to all those bands, Basie, Ellington.” Her volume was legendary; once an engineer was obliged to mike her as if she were a five-piece chamber group. She enjoyed her glory days; as her children Billy and Jackie remember, pullman porters, notoriously aloof toward most black passengers, treated her like a queen. She inspired a slew of great singers, many of them male. Brother Joe May, “The Thunderbolt of the Middle West,” mimicked her vocal dynamics and her semaphoric gestures to the point that we need his recordings to learn how she sounded. Likewise, we must listen carefully to her many other disciples -- Edna Gallmon Cooke, J. Earle Hines, Martha Bass -- to get a sense of her individual power.

Her tragedy is that she recorded too late. Even her 1950 recordings display a huge voice, ravaged by singing too hard in toomany cold rooms. By the time I was lucky enough to produce an album by her (in 1973), it was a dim echo of her regal powers.

It must have been devastating to see all the young singers running away with her sound. She never got over the fact that Brother Joe May used her adopted daughter, Bertha (who accompanies her in this movie) toaccompany him on his first recordings, all of them covers of her most famous songs. He became king of the road, and she became a beloved local figure. As you see in the movie, her children never got over her loss in status. (“They have no idea who she is.”) But she could take it, perhaps because she was so devoted to her younger acolytes in the Dorsey convention. Her evangelical work satisfied her “down in my sanctified soul.” She also dreamed of going on the road with her children. “If we got a chance,” she once told me, “nothing out there could beat us.” (Her best performance, to these ears, is ‘Never Turn Back,” a Dorsey classic in which her children give her a solid, close harmony support.)

Say Amen, Somebody made her a star. Even at the first screenings, she was mobbed by young fans. “I believe if I’d raised an altar call, many souls would have been saved.” In her last years, she remained an active member of the Dorsey convention and continued to sing at local programs. Dorsey’s death hit her hard. When I called her, she volunteered to sing “Remember Me,” the song she quotes at the movie’s end: “not just for me but for the work I’ve done.” But she couldn’t finish. “I’m sorry, l’m thinking back to those days when the people were real. You know those people lived and died for something.”

She died barely a year later, spending her last clays in the same nursing home where Bertha resided. T he two died virtually a day apart. Jackie and Billy continued to represent their mother. They had inherited much of her vocal power but, sadly, not her longevity. Billy took ill, and Jackie nursed him to the encl. A few months later, I received a call informing me that ‘’.Jackie Jackson would like you to know and wants you to know that she expired a week ago.” As if Jackie were holding up the family banner from the grave. Her death too had its mythic note. As she lay in a coma, her friends gathered by her bedside and played a video of her last performance. At the very moment where the televised Jackie herself began rejoicing, on screen hollering out “hey hey” in her mother’s cadence, the comatose patient slipped away. It was a gospel singer’s death, as could have been imagined by Mother Smith herself.

Eugene Smith, another of Roberta Martin’s students, has an impious but shrewd take on the father of Gospel: “Dorsey is our greatest writer. He can’t sing ‘em, and he can’t half-play ‘em. But he’s the foundation.” As you can hear when Dorsey performs “When I’ve Done The Best I Can” (a tune heavily indebted to Irving Berlin), he had a slight, tremulous voice which frequently soared into a reckless fa lsetto, lying somewhere between an Irish tenor’s croon and a yodel. Perhaps this is because his earliest singing inspiration was Homer Rodeheaver, a white tenor, who sang with the barn-storming evangelist, Billy Sunday (whose vaudevillian stunts and financial acumen both impressed the young Dorsey).

During the 1920s, even as he enjoyed considerable success as both a soloist and as Ma Rainey’s accompanist, Dorsey kept composing gospel songs. By 1929, he had composed his first masterpiece, “If You See My Savior,” a song that swept black churches and would later be thrillingly interpreted by singers like Mahalia Jackson, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and Marion Williams. He returned to the church, content with a smaller income but greater spiritual rewards. Then came the tragedy of his life, ilie death in childbirth of his wife and infant son. The events shook Dorsey, and he contemplated returning to blues. In his darkest hour, Dorsey claimed, he was inspired to write his most famous song, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.”

It’s safe to say that until the last twenty years and the triumph of Contemporary Gospel, “Precious Lord” would prove the most popular of all gospel songs, one almost as beloved as the Sunday School hymns, “Amazing Grace,” “Must Jesus Bear tl1e Cross Alone” (from which it swiped its chord changes), and ‘’.Jesus Keep Me Near the Cross.” Born of tragedy, it would become identified with an even greater tragedy. In 1968, shortly before his assassination, Dr. King requested that Ben Branch, a tenor saxophonist, perform “Precious Lord” at the next service. The song entered American history as Dr. King’s last request; for some people, it will always be identified with his death. A few days after the assassination, I heard Marion Williams sing the song in memory of her leader. When she reached the climax, she ad libbed, “I imagine that Dr. King thought in his mind as he stood over that balcony, ‘At the river, lord, I ‘II stand, Guide my feet, hold my hand,”’ as powerful and terrifying a vocal blast as I’ve ever heard. Fifteen years later I had a chance to produce “Take My Hand Precious Lord: The Beloved Gospel Songs of Thomas A. Dorsey,” an anthology of new recordings of Dorsey’s masterpiece. The album opens with Dorsey’s recital of the events that led to the song’s composition followed by Williams’ performance; in 2003, the album was one of the first fifty selected by the Library of Congress to enter the National Registry. It was also the only gospel record among that first group. A final historical imprimatur, as if, by then, the song needed it.

Within the film, Dorsey performs it at a meeting of the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses. He chooses to include a later verse (“Precious Lord, I love your name, Looking back from whence I came”). Even with his skimpy, aged voice, he is riveting. The great Dorothy Love Coates saw S<ry Amen, Somebody in Birmingham. “I can’t explain it. When Mr. Dorsey sang that verse, and that poor woman fainted, I screamed. I forgot I was in a movie theater. Maybe it was knowing how old and sick he was. Maybe it was thinking of Dr. King. But, brother, those people took me to church.” Hers was not a unique response.

Actually most of Dorsey’s songs are bouncier than “Precious Lord.” The sly syncopations he brought into gospel were not universally accepted. As he remembers, many pastors objected to the blatant echoes of the blues (Willie Mac Ford Smith was accused of using “coonshine” and “ragtime” devices; Mahalia Jackson was kicked out of churches for shaking her sanctified booty). But the music was accepted so quickly that the ministers, all of them with eyes on the prize, eventually welcomed him and Sallie Martin. In addition, Dorsey’s lyrics instilled a powerful sense of vocation. Consider “Singing in My Soul,” performed early in the film by Willie Mae Ford Smith. Not to mention oilier Dorsey titles like “I Thank God for My Song” and “I’m Going to Live the Life I Sing About in My Song.” Dorsey gave singers enough confidence to challenge the preachers. The Baptists and Methodists relented. Meanwhile the holiness churches feasted off Dorsey’s songs, as if they were classier versions of their rollicking shout songs. Which they quite deliberately were. As a preacher’s son, Dorsey knew all the familiar lines, textbook and folkloric, tunes, and beats of all the denominations, His ecumenical approach opened the Convention to Baptists and Pentecostals alike, despite their years of bitter feuding.

Dorsey composed more gospel standards than anyone, at least sixty. By 1935, he had already produced “Changes” (a reworking of “There’ll Be Some Changes Macie”), “How About You,’’ “If You See My Savior,” “I’m His and He’s Mine,” “Precious Lord,” “Some Day, Somewhere,” “Shake My Mother’s Hand for Me,” “Singing in My Soul,” “The Old Ship of Zion,” “Traveling On,” “When I’ve Done My Best,” and “When the Gates Swing Open,” as well as rearranging (usually w-ith new verses) a host of traditional spirituals and evangelistic songs. Had he stopped then, it would have been enough. In 1938, Sister Rosetta Tharpe scored gospel’s first cross-over hit with a Dorsey song, “Hide Me in Thy Bosom,” which she provocatively retitled “Rock Mc.” By that time white evangelists had started including Dorsey tunes in their services. In fact, the biggest paydays of Dorsey’s lifo came from Reel Foley’s recording of “Peace in the Valley” and Elvis Presley’s recordings of both “PreciousLord” and “Peace in the Valley.” Those songs became as popular with southern white congregations as black. Indeed, many a segregated service would end with tear-filled renditions of Dorsey’s songs. (How many songs have played so dominant a role in both cultures?)

Dorsey collected some royalties -- his songs would be falsely claimed by numerous singers, black and white, as their own compositions -and let the matter slide. If Sallie Marlin had stayed with him, he would have grown far richer. But then she might have driven him crazy. Instead he e,tjoyed a long life with the devoted companionship of his second wile, Kathryn. Especially during ilie last, very difficult years, Mrs. Dorsey was the most dedicated helpmate imaginable. Even then, on his sickbed, the old man might breathe out a falsetto moan of “Precious Lord.”

Three days before Dorsey’s death, his wife tried to rally him by singing the song. For a moment, he opened his eyes, “and with that finger, he started to direct me.” Everyone who sees the film will know what she means.

Kathryn Dorsey puts it best: “You had to love Sallie Martin to like her.” Feisty and crotchety, she was notorious in gospel circles for being one very tough customer. When Dorothy Love Coates asked how an eighty year old Sallie would manage a crosscountry car trip on her own, she replied, “Baby, it’ll be nobody but me, the lord, and the gun.”

She had been raised on a farm but always bad an inquiring mind. “I had read this here Sears catalogue, and I told my folk, see if l’m don’t wear that stuff.” Years later, in a train station, a white woman stepped up to Miss Martin and stroked the several fur coats she was holding. “Are they real, girl?” “Yes,” she replied. “T hey’re real. They’re mine. l ‘m Sallie Martin and the lord gave them to me.”

Sallie had not intended to sing in the film But when Dorsey chimes in with his 1932 recording of “If You See My Savior,” she harmonizes in a soft, refin ed contralto, quite unlike the raucous holler which had shouted in so many churches. “Beautiful, my child,” says Dorsey, obviously moved. But Sallie makes it clear that: she won’t sing again. The relation between Sallie and Dorsey was something lo behold. She kept fussing at him, as if they were still road partners; for all the world, it was the behavior ofa woman scorned. Yet he always humored her, and they continued to direct the convention long after their professional separation. I was able to record Sallie, accompanied by Dorsey, for the “Precious Lord” album, and in 1975, I produced a concert for the Newport Jazz Festival, which reunited the two. Neither his piano chops nor her voice had improved with the years. It made no difference. The audience at Carnegie Hall was as enthralled as folks had been at the Baptist conventions of yore.

In all her ornery splendor, Sallie Martin was one of gospel’s mythic figures. Her last years, alas, were grim. She had bad luck with men . At one time, she found herself virtu a lly homeless. With tremendous magnanimity, considering her ineluctably fractious disposition, Kathryn Dorsey’s sister Lelia Kenerson took Sallie into her home, along with the assorted furs and gowns. At the very end, Mrs. Dorsey herself offered to keep Sallie in her living room. Instead, she died, isolated and forlorn, in a Chicago hospital.

It’s a mark of the magic that Sallie and Dorsey made in the 1930s that when Mahalia Jackson, incomparably the superior singer, replaced her, the people demanded Sallie back . Instead, she toured for a few months with Roberta Martin’s group (briefly renamed The Martin and

tvlartin Singers), then founded her own group (whose first lead singer was Dinah Washington) and a publishing company together with her newest partner, Kenneth Morris, who was for several years Dorsey’s greatest rival.

As late as 1979, aged 83, she appeared in “The Gospel Caravan,” a musical starring Marion Williams, that ran for several months in Paris. Some nights she performed stiffly, and the response was demure. Other times, the spirit kicked in, and she let out a patented shriek, three octaves above her usual deep contralto, followed by a set of spasmodic twists. T hen, as always, business picked up, and Sallie Martin continued to rock and wreck.

Shortly after graduating from Englewood High School, Delores Barrett (renamed “Delois” by her husband, Reverend Frank Campbell) became the fi rst soprano vocalist in The Roberta Martin Singers. She had dreamed of becoming an opera singer and had even sung the role of Aida in school productions, although, to this day, she cannot read music. But her father, an even sterner patriarch than her husband, didn’t want her to leave Chicago. She compromised

by becoming a “beautiful singer”: Marion Williams once said, “That girl can make a song so sweet you want to eat it.” Only with the years did she acknowledge the hard-driving, house-wrecking gospel sound that now prevailed. By the time she and her sisters Billie Greenbey and Rodessa Porter were ready to become a professional group, Delois had become a champion growler, the rollicking antonym of her earlier persona.

Thanks to Say Amen, Somebody, The Barrett Sisters became international stars. The film paid off for them as it couldn’t have for their more aged co-stars. By now, they have tou red Europe, Australia and Africa several times. T hey have frequently appeared before the largely white (and Republican) Bill Gaither ensemble as well as the Prairie Home Companion, whose liberal audience would be the polar opposite of Gaither’s. Yet much like Thomas A. Dorsey’s ballads, the Barrett Sisters transcend political and sectarian divisions. Delois’ eightieth birthday drew a huge gathering, as if Chicago had finally recognized her as its living treasure. Success came very late for her but she recognizes that so many of her equally talented peers died virtually unknown.

Delois’ conflict with her husband is one of the film’s memorable scenes. It wasn’t so much that Frank didn’t want her to have an independent career as he dreamed of them being a husband-and-wife team, her songs setting the crowd up for his sermons, much as they do in the filmed sequence in his storefront church. Still the movie captures the hard road gospel women once had to travel. See Mother Smith’s barely contained outrage when her grandson declares that women shouldn’t preach. (“Oh dear God did not take me out of the man’s back.”) One gospel singer told me, “There are two kinds of men in gospel. A good man won’t understand my having a career. And the other kind will work me to death.”

During gospel’s golden age, male quartets were at least as popular as the female gospel singers. In order to keep up with those hard-singing men, the women had to cultivate all the tactics of a male preacher. Growling and moaning usually coarsened their voices. Bnt shouting the house was the name of the game, and crooning wouldn’t do the job. In order to make her way, a gospel woman had to sing like a man. Sometimes think and curse like one, as well. During the years of her vocal prime, Delois was a housewife, raising four children (two of whom have pre-deceased her). But she believes that the hard singing required of gospel professiona ls back in the day would have destroyed her. “Maybe folk like Mother Smith and me weren’t meant to be like Mahalia or Clara Ward.” She doesn’t mention thatjackson died at 59 and Ward at 48 while Mother Smith carried on into her eighties.

As her voice drops and darkens with age, she turns more to the sadder, deeper gospel tunes, quite unlike the lilting, neo-operatic ballads of her youth. “I think a lot about those folks . Dorsey and Sallie and Willie Mae. T hey were old when I was young, and now I ‘ve almost caught up with them. It tears me up to think of Roberta Martin and the Martin Singers, Norsalus McKissick, Bessie Folk, Myrtle Scott, and my dearest friend, Robert Anderson. Can you believe that they’re all gone? I never thought I’d be the last one.”

Since the debut of Say Amen, Somebody, gospel has changed drastically; it was definitely not Sallie Martin’s gospel, and not even Mahalia Jackson’s. The harmonies and rhythms are more complex, the vocal stylizations far more elaborate. (The intricate melisma is not to everyone’s fancy. I have dubbed it “the gospel gargle” and “the Detroit disease. In a more painful version, it has become the ubiquitous sound of “American Idol.”) More money has been earned than Sallie Martin could have imagined. Yet Contemporary Gospel has yet to produce singers of the caliber that came up in her day.

The movie does include two younger acts, the soloist Zella Jackson Price, a protege of Mother Smith (who tries to prepare her for the toils and snares that await her on the road) and The 0’ Neal Twins. Edgar and Edward were born in 1937, making them a good decade younger than The Barrett Sisters. Their robust sound is closer to Contemporary Gospel. Yet their roots are evident. They got their first breaks at the Dorsey convention, and their sound is frankly indebted to James Cleveland, the late King of Gospel, who was a child prodigy/protege of Thomas A. Dorsey, and even recorded with Sallie Martin. T he 0’Neal Twins’ version of ‘’.Jesus Dropped the Charges” may be the most ex hilarating performance in the movie, youth winning out for the moment. But like so many gospel singers, their career was ill-starred. Edgar, who led most of their tunes, died in 1993, and Edward has retired.

So among the several inspirations of George Nierenberg’s film is the sheer endurance of its stars. Many singers have grown rich off the gospel sound, but how

many will last as long as Dorsey, Willie Mae, Sallie, and their spiritual daughter, Delois? Holding on until the end -- who couldn’t say amen to that?

—Anthony Heilbut