View larger

View larger

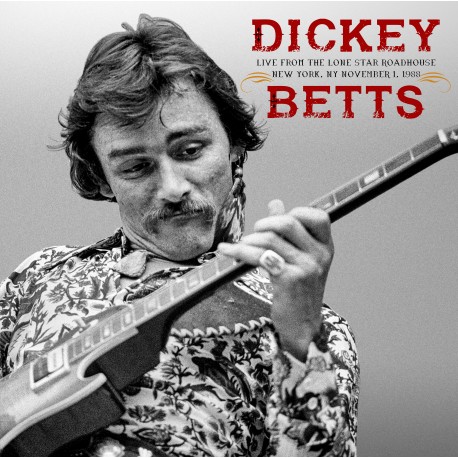

Dickey Betts - Live from the Lone Star Roadhouse

New product

Dickey Betts - Live from the Lone Star Roadhouse. Available on CD and LP.![]() bandcamp

bandcamp

More info

Track List:

- Blue Sky

- In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed

- Duane’s Tune

- Jessica

- Statesboro Blues* 7:16 2. One Way Out

- Rock ’n Roll Hoochie Koo

- Spoonful

- Southbound

Once upon a time, for a New York minute, the Texan-hearted had Big Apple homes at two joints called the Lone Star.

For even the most cynical city dweller, the Lone Star Café was hard to ignore. Opened in 1976, it stood at Fifth Avenue and 13th Street — just yards from the swells at Forbes — in the hardscrabble façade of a building one might fly from after one wrong word too many. A 40-foot iguana named Iggy ruled its roof. Beneath his feet, a slogan, splayed over the top three windows: Too Much Ain’t Enough.

But in 1988, it was winding down, a fond-if-raucous memory. In its place emerged a second location, the Lone Star Café Roadhouse, next to the Neil Simon Theater in midtown Manhattan. It boasted an expansive Tex-Mex menu, walls of Gibson guitars, and an exterior accented by an old Silver Eagle bus. Yet despite its more upscale trimmings, the roadhouse and its sister were kindred spirits, with packed music calendars and a strict adherence to the too much/not enough balance.

Dickey Betts, a staple at both venues, appreciated that philosophy and explored it to the hilt one November evening, barely four months into the new Lone Star’s existence. “We’ve got a big night for ya,” he promised, then blew the paint off the walls with new songs, stone-hot classics, special guests, and accompanists he picked from the stars — a musical family that, together and apart, has helped shape and define the jam scene for the last 30 years.

Betts was back in the driver’s seat. The legendary Allman Brothers Band — with whom he’d made his name as a composer, vocalist, and guitarist, his distinctive tone a down-home purr of rock, jazz, country, and blues — was six years into its second hiatus. His other storied crew, Great Southern, would remain in limbo for the next two decades. Betts himself hadn’t released any new music since the late ’70s (the Night album, recorded in 1981, remains shelved).

But all of that changed with The Dickey Betts Band, a multi-talented union of specialists and up-and-comers. Drummer Matt Abts had become a trusted part of the fold in 1984, having backed Betts, ABB pianist Chuck Leavell, and vocalist Jimmy Hall in BHL. Johnny Neel’s keyboard work was a fixture on the Nashville circuit. Marty Privette brought not only his formidable bass chops, but also news of a young guitar-slinger with lungs and a reputation to match. And so it was that Warren Haynes became Betts’ dexterous accomplice/sparring partner, equally at ease in down-home flights and bruising rock ’n’ roll. (Haynes and Neel would follow Betts into the reunited Allman Brothers Band in 1989, where the former, minus a three-year absence, remained to the end. During that time, Haynes also launched the influential Gov’t Mule, spreading jams to the next generation with Abts behind the drums.)

This foursome erupted in late ’88 with Pattern Disruptive, recorded that spring at Allman Brothers bandmate Butch Trucks’ Pegasus Studios in Tallahassee, Florida. Overall, the album was a revivifying statement of purpose, a triumphant return for an artist in his second decade but nowhere near his creative twilight. For fans, it was worth the wait.

As great as they sounded on record, of course, Betts and friends were best experienced live, and we have the visionaries at New York’s WNEW-FM to thank for this rare opportunity to hear this lineup unchained, interpreting Betts’ Allman Brothers catalog with reverence and vigor. Neel’s ivory stabs punctuate “Blue Sky” with a rowdy roadhouse flair. “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” sways to life like a slow-rising sun, its expanse welcoming fresh shades in Abts’ thunderous interludes and Haynes’ volcanic urgency, making the 18-year-old instrumental at once familiar and au courant — a trait shared by Pattern Disruptive’s “Duane’s Tune,” named for Betts’ musical brother, the near-mythical Duane Allman, lost too soon in a 1971 motorcycle accident. Haynes and Betts revive that twin-guitar frolic, honoring past glories — sometimes uncannily — while charting new realms. After that display, anyone still skeptical of Haynes’ bona fides was likely silenced for good by the duo’s exquisite precision on the always glorious “Jessica.”

Unbeknownst to the audience, more giants waited in the wings. Rick Derringer surfaced first, adding his own six-string fire to “Statesboro Blues” and “One Way Out” (more blues explosions than jams), then uncorking a scalding “Rock and Roll, Hoochie Koo,” with its nod to a band called The Jokers, which happened to feature a young Dickey Betts on guitar. If Derringer wasn’t enough, Betts then called bass god Jack Bruce (Cream) and slide specialist Mick Taylor (The Rolling Stones, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers) to the stage for “Spoonful,” presented a la Cream as a pulsing stagger more insidious than the Howlin’ Wolf original, and “Southbound,” an all-hands-on-deck closer fat with funk punches, barrelhouse sanctification, and four-alarm rock ’n’ roll — the best of all worlds in an 11-minute marathon.

Was it all too much? No, on the contrary: The Lone Star clamored for more. You will too, guaranteed.