View larger

View larger

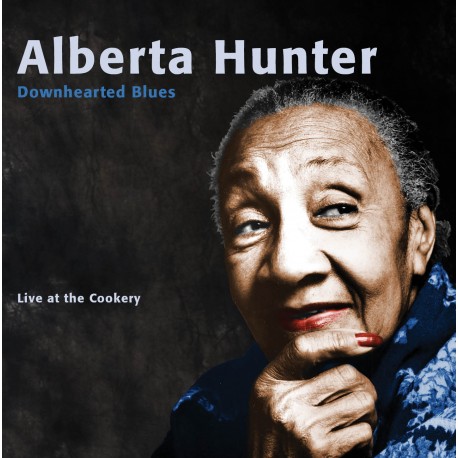

Alberta Hunter: Downhearted Blues, Live At The Cookery

New product

What an amazing life Alberta Hunter led. Settle into a front table at the Cookery and revel in her regal presence once more, because it’s showtime!

—Bill Dahl

More info

It’s difficult to ascertain the most remarkable facet of pioneering blues chanteuse Alberta Hunter’s incredible career. Was it her role in the vanguard of the “classic blues” movement of the early 1920s, when she recorded prolifically for Paramount and other labels during the industry’s first foray into the idiom? Her overseas entertain grateful U.S. troops during not one war, but two? Or her heartwarming late 1970s/early 1980s comeback on York cabaret circuit after more than two decades away from singing professionally, when she was well into her 80s? One fact is inescapable: when she died on October 17, 1984 in New York at age 89, Hunter was a genuine star once more.

Born April 1, 1895 in Memphis and weaned on spirituals and W.C. Handy’s pioneering blues, Alberta was on the move in her teens, riding a train to Chicago in the company of her female schoolteacher without bothering to obtain her mother’s permission. The Windy City was wide-open and full of opportunity. By age 16 Hunter was singing pop tunes of the day at a joint known as Dago Frank’s (political correctness was still a long way off), and later at Hugh Hoskin’s and the Panama Café. Times were good at the end of World War I; Alberta was in the midst of a celebrated five-year residence at Chicago’s ritzy Dreamland, singing in front of New Orleans jazz great King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band with Louis Armstrong.

In the wake of “Crazy Blues,” Mamie Smith’s groundbreaking 1920 smash for OKeh that was the first “race record” sensation (ushering in the era of “classic blues” singers “Ma” Rainey, Sipple Wallace, and Bessie Smith), Alberta made her studio bow in May of 1921 for Black Swan Records, a short-lived venture run by Harry Pace and W.C. Handy that was one of the first black-owned labels. In the company of pianist Fletcher Henderson and his “Novelty Orchestra” (their ranks included Barney Bigard and Don Redman), Hunter debuted with “How Long, Sweet Daddy, How Long” b/w “Bring Back The Joys” and encored with the popular “Some Day Sweetheart (You’ll Be Sorry)” b/w “He’s A Darn Good Man (To Have Hanging Around).”

Alberta moved to Paramount Records in July of ‘22, cutting a half dozen sides that included her original “Down Hearted Blues,” which she wrote with piano accompanist Lovie Austin and forcefully revisits here. (Bessie Smith, the immortal “Empress of the Blues,” ended up scoring a bigger hit with “Down Hearted Blues” as her Columbia debut in February of 1923, selling some 800,000 copies.) Alberta recorded prolifically for Paramount into early 1924. Henderson’s orchestra usually backed her in the studio, though “Stingaree Blues.” cut in mid-1923, found Hunter backed by pianist Fats Waller. Alberta struck a blow for musical equality that February by recording four sides (including “Tain’t Nobody’s Biz-ness”) with the Original Memphis Five, a white band led by trumpeter Phil Napoleon. At her final Paramount date in February of ‘24, Hunter cut “Old-Fashioned Love” with the E Jubilee Quartette.

Having conquered Chicago, Hunter had moved to New York in 1923; joining the cast of the Broadway production How Come? She continued to record for Gennett in ‘24 (with Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet in support as part of the Red Onion Jazz Babies), Okeh in 1925-26, Victor in ‘27, and Columbia in july of 1929 (where she implored her man to “Gimme All The Love You Got”), and tirelessly worked the vaudeville circuit. When the classic blues trend had run its course, Alberta ventured over to jazz-obsessed France in 1927, and co-starred with the great Paul Robeson in a 1928 London stage production of Showboat that was a sensation.

Overseas audiences continued to be captivated by Hunter’s cabaret act. She headlined in Paris and at London’s Dorchester Hotel in 1934, recording a dozen standards with Jack Jackson’s Orchestra for HMV, made her cinematic bow in a stunning production number within the British film Radio Parade of 1935, and travelled as far afield as Egypt (where her photo was taken astride a camel in the desert). But when she came back home, recording offers were scarce, apart from four unissued trial recordings for ARC in 1935 (including her original recording of the bawdy “You Can’t Tell The Difference After Dark”), six solid sides for Decca in 1939 with trumpeter Charlie Shavers that included a cover of Billie Holiday’s “Fine And Mellow,” and four 1940 efforts with pianist Eddie Haywood for Bluebird (notably her first stabs at “The Love I Have For You” and the swinging “My Castle’s Rockin’”).

Alberta hosted her own New York radio program during the late ‘30s, and Broadway welcomed her back in 1939 when she shared the stage with Ethel Waters in Mamba’s Daughters. When World War II broke out, the singer bravely served her country in the USO, entertaining troops in Europe, China, Burma, India, and the South Pacific. Hunter and her troupe even had a chance to entertain General Dwight D. Eisenhower, British Field Marshal Montgomery, and Soviet military leader Gregory Zhukov at Eisenhower’s Frankfurt, Germany headquarters in 1945. She was eventually awarded a Medal for Meritorious Services for her patriotic efforts, and continued to heed her country’s musical call all the way into theKorean conflict.

There were scattered post-war sessions, a couple of 1946 platters for the Juke Box logo (including the timely “He’s Got A Punch Like Joe Louis”) and another pair for Regal in 1950 with saxophonist Budd Johnson and guitarist Al Casey (including “I Got A Mind To Ramble,” remade for this collection). Her beloved mother died in 1954, and after co-starring in the 1956 Broadway flop Debut, Alberta bowed out of performing to train as a nurse. Upon graduation in 1957, she commenced a new career at New York’s Goldwater Memorial Hospital at age 62, a stage when must folks are contemplating retirement (she told the hospital’s administration she was 50).

Other than a couple of Chis Albertson-produced LPs cut two weeks apart in the summer of 1961 (Songs We Taught Your Mother, a set for Prestige’s Bluesville subsidiary that showcased her alongside Lucille Hegamin and Victoria Spivey. and an album for Riverside, Chicago: The Living Legends, that reunited her with Lovie Austin and Lil Armstrong), she determinedly kept a low profile for more than two decades, concerned the hospital would learn how far past mandatory retirement age she actually was and let her go.

Alberta was bored and depressed after being forced by hospital regulations to finally hang up her stethoscope in 1974. But musical pursuits called once again when Barney Josephson invited her to star for six weeks at the Cookery, his hip Greenwich Village cabaret, in October of ‘77, she introduced herself to an entirely new sensation of fans who embraced the octogenarian as the irreplaceable life force she was. After that, things happened fast. With the equally legendary John Hammond at the production helm, Hunter cut an album’s worth of her classics (and a few new ones) for the Columbia soundtrack of director Alan Rudolph’s moody 1978 film Remember My Name (starring Anthony Perkins and Geraldine Chaplin). Dick Cavett and Mike Douglas invited Alberta to brighten their TV talkfests, 60 Minutes profiled her, and she sang for President Jimmy Carter at the White House. Buoyed by the commercial and critical acclaim, Columbia had her cut three more albums: Amtrak Blues (1980), The Glory Of Alberta Hunter (1981), and Look For The Silver Lining (1982). Alberta’s voice was in fine shape, the sis decades in between her first recordings and her last, only heightened her natural charm.

These live recordings are from one of her many triumphant evenings at the Cookery. Her sense of swing and theatricality remained impeccable and with longtime pianist and arranger Gerald Cook, and sturdy upright bassist Jimmy Lewis providing sterling accompaniment, Alberta glided through saucy double-entendre-loaded numbers (“Handy Man,” “Two-Fisted Workin’ Man”), time-honored standards (a rip-roaring “I Got Rhythm,” the tender “Georgia On My Mind”), and the touching ballads “The Love I Have For You” (from Remember My Name) and “You’re Welcome To Come Back Home.”

Track List:

- My Castle’s Rockin’

- The Love I Have For You

- I Got Rhythm

- Downhearted Blues

- Time Waits For No One

- I’m Havin’ A Good Time

- Two-Fisted Double-Jointed Rough And Ready Man

- The Dark Town Strutter’s Ball

- Sometimes I’m Happy

- I’ve Got A Mind To Ramble

- Old Fashioned Love

- You Can’t Tell The Difference After Dark

- Remember My Name

- When You’re Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With You)

- Georgia On My Mind

- Handy Man

- Never Knew My Kisses

- You’re Welcome To Come Back Home