View larger

View larger

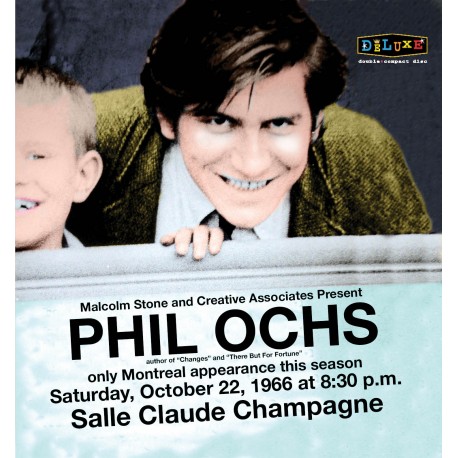

Phil Ochs live In Montreal, October 27, 1966

New product

This Montreal gig was smack dab between his final Elektra album – Phil Ochs In Concert in March ’66 – and his first release for A&M Records – Pleasures Of The Harbor in November ‘67.

More info

It’s December 22nd, 2016 as I type these words, my attention split between a concert Phil Ochs performed on October 22nd, 1966 in Montreal and the fact that a neo-fascist con man with gilded hair and gilded toilets has been elected President of the United States. A numerologist might read into the symmetrical signage: 50 years twixt the concert and my fingers tapping on these keys, 10 years between the concert and Phil’s death in 1976, exactly 30 days before the inauguration, and two dates both falling on the 22nd. So many even numbers during such an odd time. But my personal thought at the moment is more down to earth: WWPD?

What Would Phil Do if he were here today?

“It’s not enough to know the world is absurd and restrict yourself to pointing out the fact. Still I am forced to go on because I don’t want the world to be left in the hands of the Hitlers,” Ochs once wrote. “This one thing I feel is a driving force: that I get repelled by certain things – or they strike me as funny, or weird or strange, or ridiculous – and my response comes out in the form of a song.”

Repelled. Funny. Weird. Strange. Ridiculous. Hitlers. These words resonate 50 years later, especially under the current political circumstance, a sad indication of how little has changed. Few songwriters mirror the moment they lived in as definitively as Phil Ochs. He was considered a folksinger and yet he didn’t rewrite Child Ballads or resurrect Delta blues. For most of his career he accompanied himself with a sole acoustic guitar, but by 1966, his lyrics became more complex, more artful and his melodies and arrangements more baroque. He’d have as much in common with Brecht and Weill as he would with Pete Seeger.

The Montreal gig was smack dab between his final Elektra album – Phil Ochs In Concert in March ’66 – and his first release for A&M Records – Pleasures Of The Harbor in November ‘67. On the former he’s still the lone troubadour, armed only with a guitar that kills fascists (to paraphrase Woody Guthrie), while on the latter he utilizes ornate orchestration and piano accompaniment ranging from classical to ragtime. In many of the renditions heard on this live set, one can hear Ochs toying with the arrangements, adjusting the tempi mid-song and applying dissonance for effect. In some instances, his ideas outrun his technical capabilities. He overcame this limitation once he got into the studio with a professional producer and arrangers.

And then there’s his voice, an instrument that could register as thin, but here in Montreal is full-bodied and blessed with one of the best vibratos in show biz. Younger brother Michael Ochs was present in Laurel Canyon one day when Neil Young told Phil that “The way you stretch notes is one of my biggest influences.” Older brother had a sui generis knack for breaking-up a word by syllables so that they fit a song’s meter, but also to emphasize the meaning of the lyrics. Again, despite the folksinger handle, the flyover country singers of his Middle-American youth had a strong influence, most audibly the piercing nasality of Webb Pierce that stemmed from the Irish tenor tradition.

Ochs’ early songs were comprised of man-the-barricade anthems designed to rouse demonstrators, as well as ripped-from-the-headline reports that led his competitive compadre Bob Dylan to critically label him a “journalist.” (As if there’s something wrong with journalists. Some of my best friends…oh never mind.) In Montreal ’66 we’re witnessing Phil’s gradual thematic transition from advocacy journalist to 20th Century Romantic poet. The newer material isn’t folk by narrow definition – call ‘em Phochs songs. It doesn’t necessarily make them any less political – for instance “Crucifixion” is about JFK’s assassination, but the author isn’t re-running the Zapruder film, he’s using metaphor as artistic tool to render political murder and in the process capture the enormity and impact of the event.

By ’66, the essence of Phil’s newer songs like “Flower Lady” and “Cross My Heart” is no different than the earlier, more overtly topical ones. The connective tissue is the effort to diminish suffering and share the universal experience of being human, ensuring that all are treated with fundamental measures of dignity and justice.

One of Phil’s strengths is his sharp sense of the absurd – a survival mechanism that helps us deal with events that straddle the tragic and ridiculous – best conveyed in his self-described “study in cynicism,” the classic portrait of apathy “Outside Of A Small Circle Of Friends.” Coupled with his ‘tween-tune patter -- and despite his profoundly serious intentions -- Phil was one funny cat.

Yet lingering throughout are portents that he endured a private suffering. He introduces “Doesn’t Lenny Live Here Anymore” as “a brand new song written only last week – it’s a study in levels of depression.” Ya wanna reach out and hug him. “My drifting days prepare me to do battle with the night,” he sings in “Song Of My Returning.” He lost that battle on April 9th, 1976 when he took his own life. But the songs endure and we have the evidence in this collection, what his archivist David Cohen calls “The best live Ochs tape.”

So here we are 50 years later, 30 days before the gilded oaf takes his oath to defend the Constitution. We’ll finish where we started, with an excerpt of Phil’s writing. He begins by quoting Greek scribe Nikos Kazantzakis: “’It is wrong to expect a reward for your struggles.’” Phil then goes on: “The reward is the act of struggle itself, not what you win. Even though you can’t expect to defeat the absurdity of the world, you must make that attempt. That’s morality, that’s religion. That’s art. That’s life.”

Attempt the act of struggle. And that’s it – that’s what Phil would do.